Une blessure affective d’Audrey Hepburn : son père, Joseph Ruston, pro-nazi anglais

28sept

Au hasard d’une émission de télévision consacrée à Audrey Hepburn (Ixelles, 4 mai 1929 – Tolochenaz, 20 janvier 1993),

j’apprends que sa relation très malheureuse à son père, Joseph Ruston (Stredocesky, 21 novembre 1889 – Dublin, 16 octobre 1980),

constitua pour elle une terrible blessure affective, toute sa vie…

…

…

Cf cet article bien documenté de Lisa Waller Rogers, Audrey Hepburn & the Family Skeletons :

…

…

Audrey Hepburn & the Family Skeletons

…

…

November 13, 2014 by Lisa Waller Rogers

…

…

…

…

…

…

Readers, at the beginning of this year, I had entertained the idea of writing a juvenile biography of Audrey Hepburn (1929-1993) and the five years she spent in Nazi-occupied Holland as an underground resistance worker. Having read many biographies on Audrey, I was familiar with the yarns about her being a courier for the Dutch Resistance movement against the German occupation and participating in clandestine dance performances to raise money for the cause.

…

…

I must say that, after scouring tons of resources -bios, interview transcripts, old Hollywood magazine articles – I am not sure that Audrey actually participated in any underground activities to fight back against the Germans. To begin with, she was only eleven years old when the war started and sixteen when it ended. Her name does not appear – nor does her mother’s – on any government list of resistance activists _ voilà.

…

…

Audrey’s Real World War II Experience

…

…

The fact that Audrey did not work in the Dutch Resistance in WWII should not detract from the knowledge that the war took a great toll on Audrey’s physical, mental, and emotional health. She suffered from the horrors of war like any other citizen in a war zone. Germans were everywhere with guns with bayonets and barking attack dogs. Everyone’s liberties were restricted. There was no way to get real news as the newspapers were controlled by the Nazis and filled with propaganda. The BBC in England broadcast reliable news but the Nazis confiscated radios. Audrey saw people executed in the streets and Jewish families loaded into cattle cars bound for death camps.

…

…

…

…

One of her brothers went into hiding to avoid being deported to a German labor camp. The other brother was deported to Germany. Her own uncle was arrested, imprisoned, then murdered as a reprisal against saboteurs _ voilà. Sometimes 900 planes a day flew over Arnhem, German, American, and British planes, often engaging in wicked dogfights and crashing nearby. The Battle of Arnhem raged in the streets of the city and outlying towns.

…

…

In the winter of 1944-1945, 20,000 Dutch people died of starvation. There was no food to eat. Schools shut down. The trains were not running so no food was being delivered. The people subsisted on a diet of 500 calories a day. They were reduced to eating bread made from flour from crushed tulip bulbs. That “Hunger Winter”, there was no wood to build a fire to warm even one room in the house. It was a very desperate time, with the Germans taking over people’s houses and forcing large groups of people to huddle together in small dwellings.

…

…

…

…

Audrey almost died from starvation. Her body, adolescent at the time, did not develop adequately and never fully recovered from the deprivations. Her rib cage was underdeveloped, and she suffered from an eating disorder all her life. She was so malnourished that her ankles swelled up and she could barely walk. She retained stretch marks on her ankles from where the skin was stretched from the edema. She suffered from anemia and respiratory problems, too.

…

…

…

…

For a long time after the war was over, she had no stamina. She would go on eating binges, as she herself said : she couldn’t just eat one spoonful out of the jelly jar. She had to eat and eat until the jar was empty ! She would then get fat, then diet herself back to rail thinness so she could compete in the worlds of ballet, modeling, stage, and screen. She forever was nervous, adored chocolate most of all, worked hard, and chain smoked, dying of cancer at the relatively young age of 63.

…

…

What They Tried to Make us Believe about Audrey’s War Time

…

…

In interviews, Audrey did not volunteer that she was a resistance worker. She didn’t really talk about the war days _ voilà. Those stories were mostly generated in the fifties by her Hollywood publicists, largely appearing in popular magazines such as Modern Screen and Photoplay. Although the stories were mostly false, they entered the public lore, were repeated in article after article, and thus acquired an undeserved air of authenticity. Some of the stories include :

…

…

- Audrey helped a downed Allied pilot in the woods. She encountered a German patrol on the way and pretended to just be picking flowers.

- Audrey was almost deported by the Germans.

- Audrey hid in a basement for a month with only a few apples to eat to avoid being picked up by a Nazi patrol who wanted her for a cook.

- Audrey delivered illegal newspapers on her bicycle.

- Audrey danced in blacked-out homes to an audience that didn’t clap for fear they would be discovered by the Nazis (Audrey claims this part is true; how many times did she do it, though, once? Also, her ballet teacher was a Dutch Nazi, so I doubt she would have approved of Audrey dancing for the Resistance.)

…

…

However, this resistance worker that braved life and limb for country and kin did not exist except in magazine articles. That Audrey Hepburn was a invention of Hollywood’s _ voilà.

…

…

The irony is that Audrey’s World War II experience needed no embellishment. It is a tale of great endurance, of courage in the face of daily fear.

…

…

The lies about her involvement with the Dutch Resistance weren’t Audrey’s fault. Myth making was show business in the fifties. Hollywood wanted control. Hollywood wanted its leading ladies squeaky clean and, if they could keep her that way, Audrey was going to be a big star.

…

…

…

…

The Hollywood image machine went into overdrive creating the myth of Perfect Audrey, the Resistance Worker, to cover up _ voilà _ the embarrassing truth about her past and her roots. They claimed her father was an international banker (a lie) and that her mother was a Dutch noblewoman (which was true, but no one mentioned that she liked rich playboys). Hollywood created this myth because Audrey Hepburn had a lot of skeletons rattling around in her closet. As it turns out, her parents – the Dutch Baroness Ella van Heemstra and her British husband Joseph Anthony Ruston — did some very bad things with some very bad people before and during World War II. And neither of them was a decent parent _ voilà _ to little and lovely Audrey.

…

…

…

…

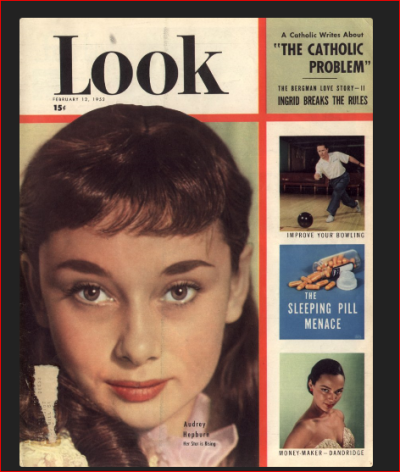

In 1953, Audrey won the Best Actress Oscar for her debut American film, “Roman Holiday” _ Vacances romaines…

…

…

Even a hint of scandal would have jeopardized Audrey’s budding career ; Americans had no stomach for Nazis. So the Hollywood image makers hid the truth.

…

…

What Her Parents Were Really Like

…

…

The truth can now be told : Audrey’s parents were devotees of the notorious British fascist, Sir Oswald Mosley, a Hitler wannabe, whose followers were called the Blackshirts (the British Union of Fascists or BUF) _ voilà. Mosley, like Hitler, blamed the Jews for all the problems Britain faced. There was no truth to this monstruous lie, but this is how fascists always derive their short-term power, by turning one group of citizens against another.

…

…

…

In October 1934, Mosley was losing steam politically so, in order to keep his following and funding, he ramped up the anti-Semitic rhetoric. At the Albert Hall in London, he addressed a huge crowd, saying,

« I openly and publicly challenge the Jewish interest in this country commanding commerce, commanding the press, commanding the cinema, commanding the City of London, commanding sweatshops.” (1)

…

…

…

…

What Audrey’s Parents Did for Her Sixth Birthday

…

…

…

…

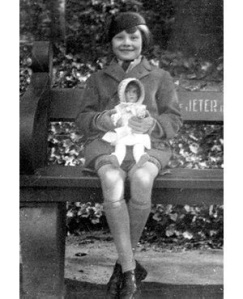

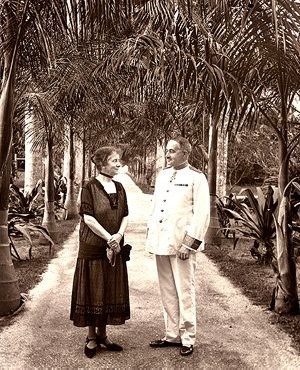

Audrey Ruston Hepburn turned six years old on May 4, 1935, in Brussels, Belgium, but neither of her parents were there with her to celebrate. Ella and “Joe” were touring Germany with a delegation from Mosley’s BUF _ voilà. They were there to observe what a wonderful job the Nazis had done in restoring the German economy. Along with the infamous Unity Mitford of England, Hitler’s lackey, they toured autobahns, factories, schools, and housing developments.

…

…

…

…

Then Audrey’s parents met Hitler himself _ voilà _ at the Nazis’ Brown Househeadquarters in Munich. A photo was taken of Ella in front of the Brown House, showing her with her friends Unity, Pam, and Mary Mitford. Upon her return, Ella put the photo in a silver frame and displayed it proudly in her home.

…

…

Shortly after Audrey’s parents returned from Germany, her father and mother had a terrible argument. Audrey’s father walked out on the family, leaving her, her mother, and her two half-brothers to fend for themselves. (This was Ella’s second marriage). Some said Joe was a big drinker and that had caused the split-up. Others said he was a womanizer, with a lover or two on the side. Worse, it was rumored that the Dutch Queen Wilhelmina had spoken to Ella’s father, the Baron, about Joe’s embarrassing politics and told him to tell Ella to end the marriage.

…

…

Chances are, though, that Joe just wanted to be free of domestic entanglements to pursue his rabid anti-Communist agenda. At that time, he was very active in the Belgian fascist party, the Rexists _ voilà. He would soon divide his time between Belgium and England.

…

…

Audrey remembers her mother sobbing for days on end, mourning the loss of yet another husband. But Ella must have recovered herself fairly quickly because, four months later, she was back in Germany with the Mitford sisters, this time, to witness the military pageantry of a Nuremberg Rally (and have a quick fling with the sexy and much younger journalist Micky Burn).

…

…

…

…

Upon her return to Brussels, Ella wrote a gushing editorial in The Blackshirt, extolling Hitler’s virtues :

« At Nuremberg…What stuck me most forcibly amongst the million and one impressions I received there were (a) the wonderful fitness of every man and woman one saw, on parades or in the street; and (b) the refreshing atmosphere around one, the absolute freedom from any form of mental pressure or depression.

These people certainly live in spiritual comfort….

From Nuremberg I went to Munich….I never heard an angry word….They [the German people] are happy….

Well may Adolf Hitler be proud of the rebirth of this great country…” (2)

…

…

Ella’s article appeared in column two of The Blackshirt. To its right, in column three, appeared this anti-Jewish propaganda fiction purportedly written by someone named “H. Saunders” :

« I walked along Oxford-street, Piccadilly, and Coventry-street last Saturday and I thought I had stepped into a foreign country.

A Jew converted to Christianity becomes a hidden Jew, and a greater menace. Jews have conquered England without a war….” (2)

…

…

What Ella did Next

…

…

In 1939, Baroness Ella van Heemstra, now divorced, moved with Audrey to Arnhem, the Netherlands, where her parents lived. Ella’s noble and esteemed father, A.J.A.A. Baron van Heemstra, had been the mayor of Arnhem from 1910-1920.

…

…

…

…

Then, in May 1940, the Nazis invaded the Netherlands. Ella and Audrey would spend the entire war years in Arnhem (1940-1945) _ voilà _, yet they would not live with Audrey’s grandparents much of the time.

…

…

…

…

Although he had, at an earlier time, been somewhat pro-German in his outlook, the Baron van Heemstra had changed his views. When the Nazis occupied Arnhem, they tried to coerce him to become the director of a disgraceful charity called Winterhulp. However, the Baron refused the post. Stung, the Germans struck back. As a reprisal, early in 1942, they confiscated many of his lands, houses, bank accounts, stocks, and even jewelry. German soldiers were quartered in his grand home at Zijpendaal and he was forced to move to his country homes in the small villages of Velp and Oosterbeek.

…

…

…

…

Ella, on the other hand, had none of her father’s integrity. She liked to drink and she liked to have a good time. The way she saw it, the Germans had all the good things that she lacked. Unlike the average Dutch person, the German officers drank real coffee and real tea and champagne. They had cars, too, and petrol to put in them, whereas the Dutch citizens couldn’t even take their bicycles out into the street without the Germans commandeering them. Ella liked the good life and the German officers could give it to her. She openly fraternized with them _ voilà _, having them into the family home, and going out with them in their cars, even crossing the border and driving into Germany for entertainment. She even organized a cultural evening in Dusseldorf, Germany, along with the regional head of the NSDAP (the Dutch Nazi Party). She was ruthless in pursuit of pleasure.

…

…

The illegal press of the Dutch Resistance suspected the Baroness of being an agent for the Gestapo (the Nazi secret police). She worked for the German Red Cross in the Diaconessenhuis (hospital) in Arnhem, nursing wounded German soldiers. Before the war, Ella had already displayed a Nazi swastika and a German eagle on the wall of her house in Arnhem. (3) She was the worst of the worst. And this is the home and the atmosphere in which she raised sensitive Audrey.

…

…

Hatred ran so high against the van Heemstra family – because of Ella’s Nazi sympathies and her collaboration with the Germans – that, when the Allies liberated Arnhem in May, 1945, the Baron had to hang his head in shame. He felt compelled to leave town and move to the Hague. (4)

…

…

…

…

With the war behind them, Ella concentrated her energies in forging ties with people who could further daughter Audrey’s career in becoming a prima ballerina, then a model, followed by a film star. They lived in Amsterdam for a time and then The Hague before settling in London.

…

…

…

…

What Joe Had Been Doing

…

…

Meanwhile, in the time since Audrey’s father had left his family, he had managed to get in a lot of legal and financial trouble. From 1935-1940, “Joe” Ruston was involved in multiple questionable business transactions that kept landing his name in the news in the Netherlands, England, and Belgium. In 1938, for example, he was being investigated by both the Belgium Parliament and the British House of Commons for his involvement in a corporation with financial ties to the Third Reich :

« Mr. Anthony Ruston, a director of the European Press Agency, Ltd. [was] alleged in the Belgian parliament to have received £110,000 from German industrial chiefs in close touch with Dr. Goebbels [Nazi propaganda minister] to publish an anti-communist newspaper.” (5)

…

…

His two business partners at the European Press Agency were a Nazi lawyer and a member of the Gestapo _ voilà.

…

…

Curiously, a year later, Anthony Ruston officially renounced and abandoned the name Anthony Joseph Victor Ruston and adopted the new name of Anthony Joseph Victor HEPBURN-Ruston. (6) Ruston claimed to have had a Hepburn relative with blood ties to James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell, the fourth husband of Mary, Queen of Scots. But the claim was bogus. True, there was a marriage to a Hepburn in his family line but there was no issue of which Ruston is kin.

…

…

Perhaps Ruston was attempting to prove his Britishness by connecting himself with a Scottish king. War clouds were gathering over Britain and Ruston was in hot water for his connections with Germany.

…

…

In June 1940, the Battle of Britain had begun, and England was earnestly at war with Germany. Anthony Ruston was arrested and imprisoned in England under Defense Regulation 18B, as he was considered an enemy of the state for his membership in “the British Union of Fascists…and as an associate of foreign fascists.” (7) He was interned for the duration of WWII _ voilà ! _, after which he settled in Ireland.

…

…

Sources:

…

(1) Dalley, Jan. Diana Mosley : A Biography of the Glamorous Mitford Sister who Became Hitler’s Friend and Married the Leader of Britain’s Fascists. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2000. p. 195

(2) “At Nuremberg,” The Blackshirt, October 11, 1935.

(3) 1557 Documentatiecollectie Tweede Wereldoorlog. Inventory number 247 Audrey Hepburn. Gelders Archive. Arnhem, the Netherlands.

(4) Heemstra, Aarnoud Jan Anne Aleid Baron (1871-1957). Huygens : Biographical Dictionary of the Netherlands. (online)

(5) “Banned Nazi Barrister ‘Plays Violin Beautifully,’” Daily Express, March 31, 1938. (Manchester, UK newspaper with leading circulation in the 1930s)

(6) The London Gazette, April 21, 1939.

(7) Public Record, reference # KV 2/3190. The National Archives, Kew, UK

…

…

Un bien intéressant éclairage sur la situation familiale d’Audrey Hepburn, de 1929 à 1945…

…

…

Ce lundi 28 septembre 2020, Titus Curiosus — Francis Lippa